1 Electronic Theses and Dissertations UC San Diego Peer Reviewed Title: China’s china : Jingdezhen porcelain and the production of art in the Nineteenth Century Author: Huang, Ellen Acceptance Date: 2008 Series: UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Degree: Ph. D., HistoryUC San Diego Permalink: Local Identifier: b Abstract: My dissertation examines the interaction between global political-economic transformations and changing concepts of Chinese art in the nineteenth century. Its focus is on the porcelain from the renowned “porcelain city,” Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province of southeast China. Jingdezhen has been the center of world porcelain production since the thirteenth century. Although Jingdezhen’s porcelain industries experienced tremendous changes and upheaval during the nineteenth century- including expanding overseas trade, decimation by the Taiping rebels in 1853, reinstatement of imperial patronage by the Qing Court during the Tongzhi Restoration – scholars of science, art, and Jingdezhen history alike rarely investigate this period. Contrary to scholarly consensus, the nineteenth century witnessed a surge in the production of texts and visual images detailing the aesthetics, technology, and manufacturing of Jingdezhen porcelain. This study focuses on the systemic production of knowledge about a material object – Jingdezhen chinaware – by tracing the global trajectories of key documents and visual images on porcelain that circulated within and across boundaries of such places as China, France, and Japan. I will highlight the circulation of such texts and visual images at crucial historical junctures of the nineteenth century, concentrating on periods of industrialization, inter-state conflict, and changing trade patterns. Thus this project will attempt to articulate the global and political processes that negotiate and re-position an object’s materiality– specifically the materiality of Jingdezhen porcelain–in relation to its visual and textual aspects. By historicizing the discourse and practices of a specific object of trade and art, especially one that was and remains closely associated with a particular place and culture, I examine how concepts of self and other find material embodiment through representative objects of culture and exchange Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. escholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at escholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide.

2 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO China s china: Jingdezhen Porcelain and the Production of Art in the Nineteenth Century A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Ellen Huang Committee in charge: Professor Joseph W. Esherick, Co-Chair Professor Paul G. Pickowicz, Co-Chair Professor Weijing Lu Professor David Luft Professor Kuiyi Shen 2008

3 Copyright Ellen Huang, 2008 All rights reserved.

4 The dissertation of Ellen Huang is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii

5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page… iii Table of Contents…iv List of Maps…v List of Tables…vi List of Figures…vii Acknowledgements…xii. Vita…xv Abstract…xvi Introduction Guo Baochang, Porcelain Objects, and the First International Exhibitions of Chinese Art, Texts on Jingdezhen: The Record of Jingdezhen Ceramics and the Development of a Canon Picturing Jingdezhen Porcelain in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Neither Empire Nor Nation: Understanding and Appreciating Porcelain in Tao Ya, Conclusion Appendix A Bibliography iv

6 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. Jingdezhen kilns location Map 2. Jiangxi province Map 3. Northern Jiangxi, Qing period (1820) v

7 LIST OF TABLES Chapter 4 Table 1. Average Annual Quantity of Export Porcelain from Jingdezhen, vi

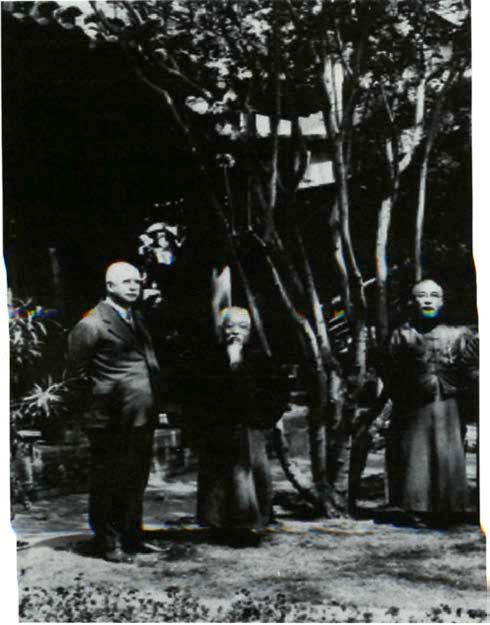

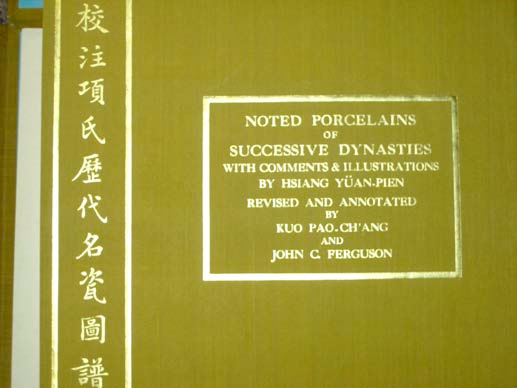

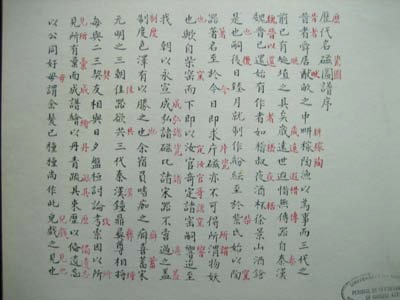

8 LIST OF FIGURES Chapter 1 Figure 1. Cover and Academia Sinica Supplement, to the Chinese Organizing Committee s catalogue of objects sent to London, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Figure 2. Actual letter accompanying catalogue given by Wang Shijie to Oscar Raphael. Fitzwilliam Museum Reference Library, Cambridge, UK Figure 3. Guo Baochang (right) standing in the garden of John C. Ferguson s (left) home in Beijing, April, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Archives Figure 4. Route map from Zhuang Yan, Shantang qingyu (Taipei: Gugong bowu yuan, 1980), Figure 5. Map of Gallery Layout Figure 6. Guo Baochang s privately printed Ciqi gai shuo. Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Figure 7. Guo Baochang inscription in gift of Ciqi gaishuo to George Eumorfopoulos, April, Figure 8. Guo Baochang s hand-written inscription on first page of Ciqi gaishuo given to Percival David, April, Figure 9. List of lectures from the Royal Academy of Arts Figure 10. Cover of translation to Guo Baochang s Ciqi gaishuo Figure 11. Top: Cover of Guo Baochang and Ferguson s Noted Porcelain of Successive Dynasties. Bottom: added portrait of the supposed author and illustrator of the catalogue, Ming dynasty collector Xiang Yuanbian Figure 12. Top: Copy of two albums of the Xiang catalogue: one with notes and one without notes by Guo and Ferguson. Bottom: example of the notes in preparation for annotation. Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art vii

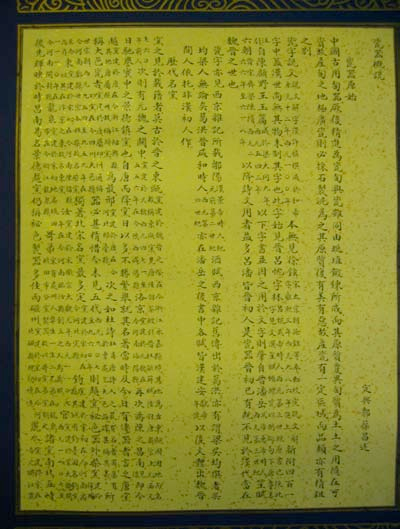

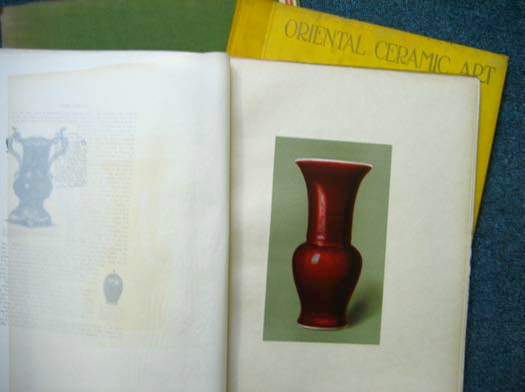

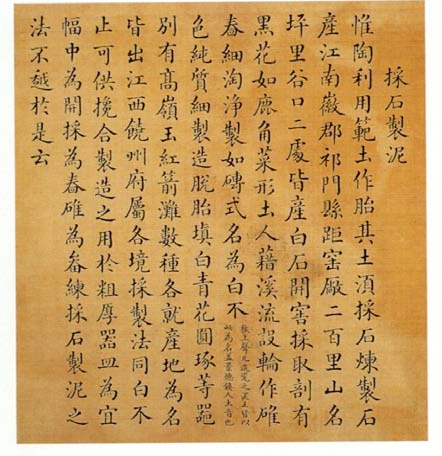

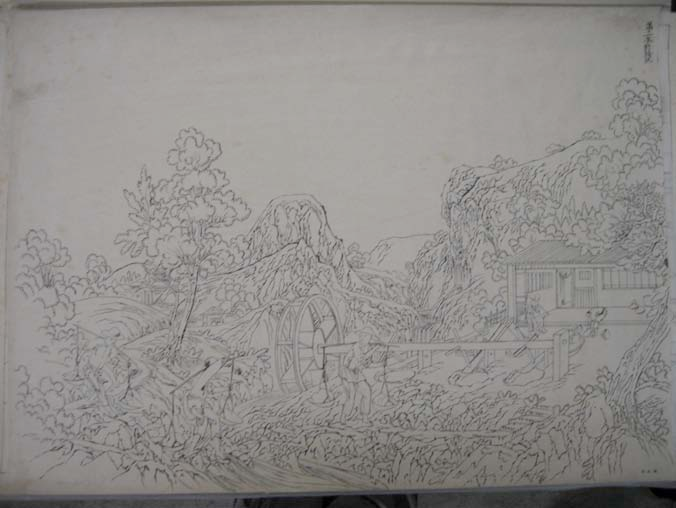

9 Figure 13. Picture of Guo Baochang s forty-volume personal porcelain collection catalogue Figure 14. Decorative stand on which Guo placed ceramic pieces Figure 15. The duobao che (car of many treasures) Chapter 2 Figure 1. Title page of second edition of Jingdezhen Tao lu, Shanghai Museum library Figure 2. Top: 1891 Jingdezhen Tao lu woodblock illustration – collecting the clay (qutu) Bottom: 1925 Jingdezhen Tao lu Zhaoji edition with new illustration collecting the clay (qutu) Figure 3. Stephen Bushell, Oriental Ceramic Art, First edition, limited to Figure 4. Example of black-and-white photographs in Stephen Bushell, Oriental Ceramic Art, Figure 5. Full-page chromolithographic plates in Oriental Ceramic Art, v. in 5 portfolios; 116 plates; 60 & 25 cm Figure 6. Last plate in Stanislas Julien s French translation, 1856, depicting China Figure 7. First plate, Collecting the clay, in Julien, Histoire et Fabrication de la Porcelaine chinoise, 1856, showing compressed vertical scene Figure 8. Inscription page signed at Tokyo Museum, in the Japanese translation, Keitokuchin tô roku, Figure 9. Last page of Temmioka Tessai s handwritten preface to Keitokuchin tô roku, Figure 10. Tiangong kaiwu woodblock illustrations: making tiles, making bricks, removing tiles from moulds Figure 11. First two woodblock illustrations in Jingdezhen Tao lu (1891[1815]), in order from top to bottom Chapter 3 viii

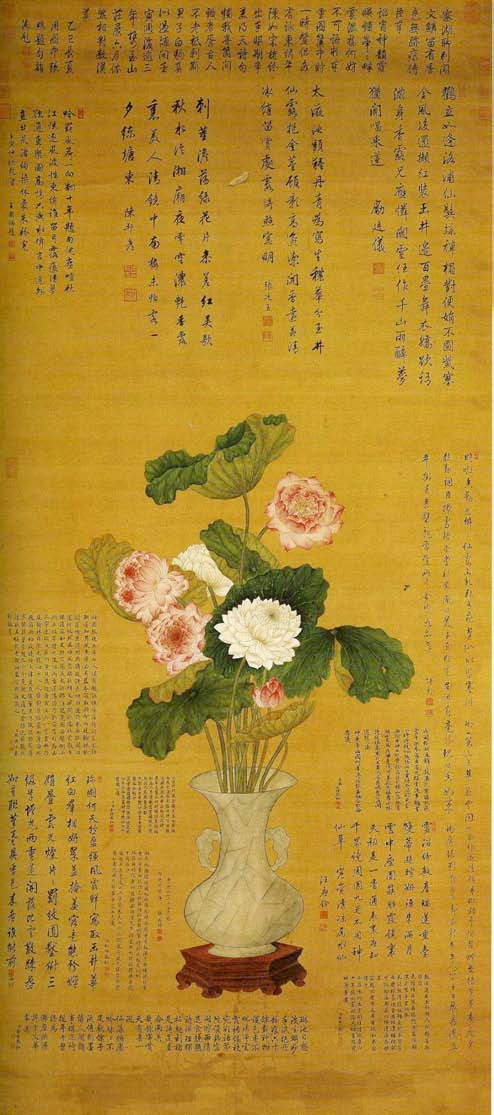

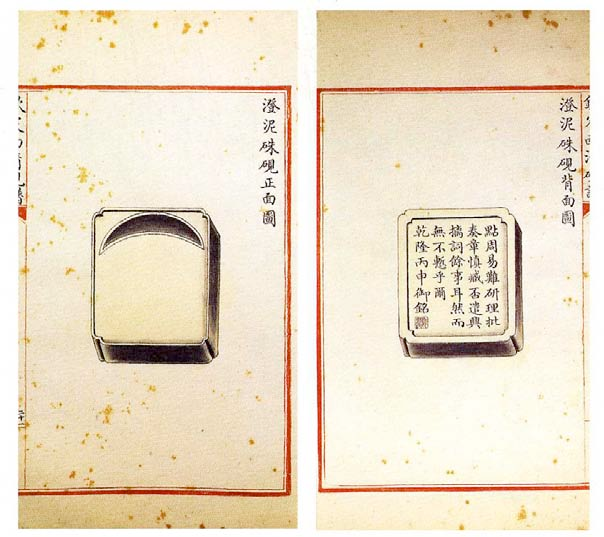

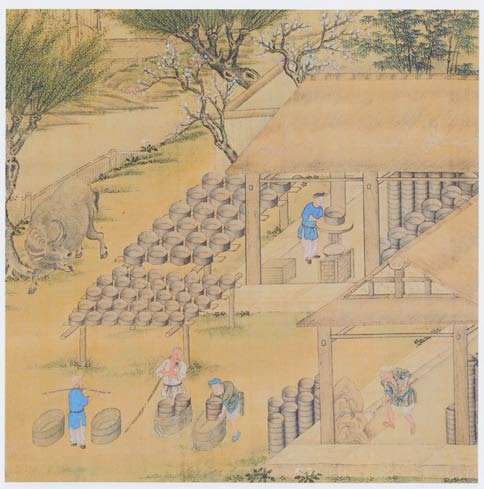

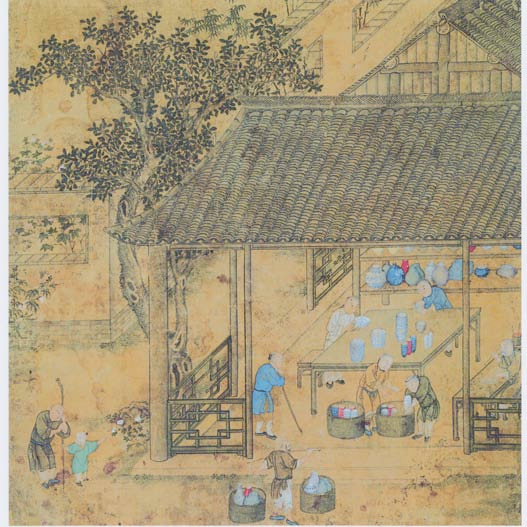

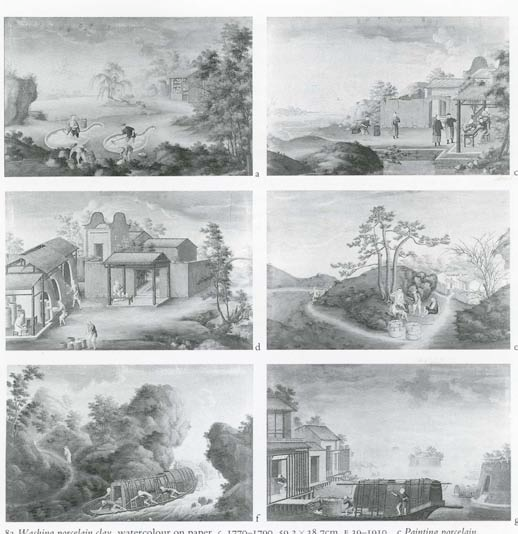

10 Figure 1. Literary Gathering (Wenhuitu, detail), ink and color on silk. National Palace Museum (Taipei) Figure 2. Lotus of a Thousand Pearls. Zhang Tingxi ( ), Qing Dynasty court painter Figure 3. Leaf from the Qing dynasty ceramic catalogue, Taoci puce, dr. circa Figure 4. The duobao ge (cabinets of many treasures) of the Qianlong period and Qing dynasty Figure 5. Two pages from Qianlong s illustrated inkstone catalogues Figure 6a. Image of text-image pairing from the album of porcelain production annotated by Tang Ying. Left: Tang Ying, Taoye tu bian ci (1743) Right: first painting leaf of album Taoye tu (circa 1730) Figure 6b. Left: Tang Ying, Taoye tu bian ci (1743) Right: second painting leaf of album Taoye tu (circa 1730) Figure 7a. First leaf of eight from incomplete painting album set Figure 7b. Second leaf of eight from incomplete painting album set. Beijing Palace Museum Figure 7c. Third leaf of eight from incomplete painting album set Figure 7d. Eighth leaf of eight from incomplete painting album set. Beijing Palace Museum Figure 8a and 8b. Leaves from export ink drawing set of 17 leaves. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Acsension # E E Gift of Mrs. Mary Goodman Figure 9. Jingdezhen taotuji. d Second painting leaf of an album set of fourteen. National Palace Museum (Taipei), guhua Figure 10. Preface to Jingdezhen taotu ji album. d First painting leaf of an album set of fourteen Figure 11. Pair of vases, circa Famille rose enamels with imperial kiln production process decoration. Shaanxi Museum ix

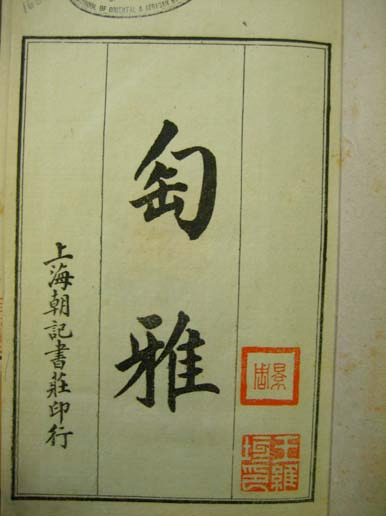

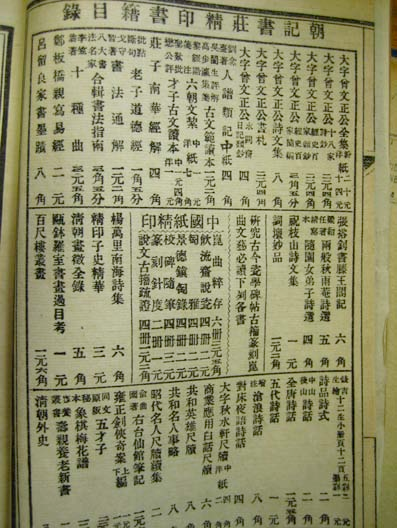

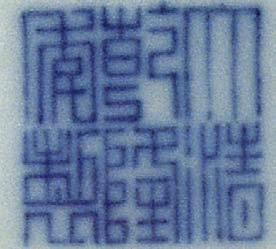

11 Figure 11a. Detail of flag bearing the phrase yuyao chang, (imperial kiln) on vase, circa Figure 12. Daoguang period large porcelain plate. Underglaze blue and white with Jingdezhen imperial kiln production process decoration. Beijing Capital Museum Figure 12a.Detail showing Daoguang period large porcelain plate, flag with characters yuyao chang, (imperial kiln) shown. Beijing Capital Museum Figure 13. Export painting set of porcelain production. 24 leaves, 7 shown, watercolor on paper, Victoria and Albert Museum Chapter 4 Figure 1. Cover of Tao Ya edition with the seal-script style calligraphy of Zhu Deyi. National Palace Museum (Taipei) Figure 2. Liu Jiaxi inscription of title page using another title, Guci huikao, for Tao Ya, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Figure 3. Edition of Tao Ya printed under the aegis of the Shanghai Society for Research on Antique Porcelain (Shanghai Guci yanjiu hui). Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Figure 4a. Advertisement for Tao Ya, Jingdezhen Tao lu, and Yinliuzhai shuo ci by publisher Zhaoji shuzhuang. Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Figure 4b. Edition of Tao Ya (mid-1920s) by publisher Zhaoji shuzhuang. Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Figure 5. Da Ming (Great Ming) Wanli mark Figure 6. Da Ming Jiajing mark Figure 7. Da Ming Zhengde mark Figure 8. Da Ming Xuande mark Figure 9. Great Qing Kangxi mark on famille verte dish Figure 10. Great Qing Yongzheng mark and pair of yellow-glazed bowls Figure 11. Qianlong mark for a covered jar with doucai glaze decoration x

12 Figure 12. Left: Mark on bottom of porcelain carving by Wang Bingrong ( ). Right: Porcelain Brush Holder by Wang Bingrong Figure 13. Chen Guozhi ( ) mark and carved brushpot made in Jingdezhen Figure 14. Snuff bottle made of carved porcelain between 1821 and 1850 in imitation of jadeite and landscape decoration. Jingdezhen. Mark: Hu Wenxiang zuo Figure 15. Wang Shaowei (active ), dated porcelain plaque decorated with qianjiang enamels Figure 16. Jin Pinqing (active ) porcelain plaque painted in qianjiang enamels Figure 17. Wang Qi, dated Porcelain plaque decorated with fencai enamels Figure 18. Pair of porcelain cups in fencai enamels with mark Jiangxi Porcelain Company ( ) Figure 19. Cover and title page of Stephen Bushell s translation of the illustrated catalogue, Lidai mingci tupu. Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Figure 20. Comparison of two translations of purported Ming dynasty collector s porcelain catalogue: text and accompanying watercolor illustration of Song Ding ware porcelain. Top: Stephen Bushell s 1908 translation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908). Bottom: Guo Baochang and John C Ferguson, trans. Noted Porcelain of Successive Dynasties (Beijing: Zhizhai shushe, 1929) Figure 21. Image of the annotation and translation process using un-illustrated Xiang Yuanbian catalogue Lidai mingci tupu original. Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Conclusion Figure 1. Floor plan of permanent ceramics galleries. National Palace Museum (Taipei) xi

13 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the energy and time of my two co-chairs, Professors Joseph Esherick and Paul Pickowicz. They have been keen critics and patient mentors. I can say with assurance that without their support, I would be unable to read my Chinese sources. I am grateful to them for supporting me throughout my personal journey and graduate education. They also made possible the cohort of Chinese history students at UCSD in the past and present, who have all stepped in to encourage and teach me along the way: Matthew Johnson, Jeremy Brown, Christian Hess, Sigrid Schmalzer, Sue Fernsebner, Cecily McCaffrey, Liu Lu, Dahpon Ho, Elya Zhang, Xiaowei Zheng, Miriam Gross, Jeremy Murray, Brent Haas, and Justin Jacobs. Professor Weijing Lu and Baomin Ye have been kind to help me with difficult translations and handwritten Chinese texts, even while I was overseas. Professor Sarah Schneewind was a careful reader and synthesizer at a time when there was no structure to the entire project; I am particularly grateful to her for her timely input. Suzanne Cahill has been an encourager of all things material and artistic, handing me relevant articles and books. Department of History Chair John Marino understood my intellectual interests. Outside of Chinese history, Professors David Luft and Stefan Tanaka have been equally as important to my growth as a student, writer, researcher, and person. They have been the sharpest of observers and critics, as well as sensitive mentors. They have unconditionally supported me in my insecurities. I thank them for sharing with me their time and insights. xii

14 Professor Kuiyi Shen came to UCSD just as I was writing my dissertation prospectus and I thank him for his mentorship, guidance, and encouragement from the project s inception. I wish he had come earlier in my graduate training his course lectures, references, and personal introductions to curators, collections, and museums have been invaluable to this project. His enthusiasm in art history has kept me in graduate school. Professor Norman Bryson and Jack Greenstein in Visual Arts also gave me critical feedback on early versions of chapters 2 and 3. Mentors at other institutions have provided crucial comments and support. I thank Professors Dorothy Ko of Barnard College, Marta Hanson of Johns Hopkins University, and Vimalin Rujivacharakul of the University of Delaware for reading chapters and outlines at crucial moments of my thinking. At conferences and over the internet, other scholars have given helpful advice and comments. I thank Teruyuki Kubo, Joe McDermott, Hans van de Ven, John Moffett, Qianshen Bai, Michael Dillon, Robert Finlay, Luo Suwen, Cynthia Brokaw, Leo Ou-fan Lee, Han Qi, Han Jianping, Lara Netting, Cheng Pei-kai, Wen-hsin Yeh and the members of the 2007 AAS Dissertation Workshop on Art and Politics. I owe much to my undergraduate advisor, Professor Frank Turner of Yale University, for encouraging me through the years. As someone who came to the subject of art history and porcelain rather late, I have needed to beseech the advice of many specialists in history of science, art history, and ceramics. I am grateful to Yu Peichin, Shih Chingfei, Peng Yingchen, and Lai Yuchih at the National Palace Museum. In England, I received much help from Stacey Pierson, former curator of the Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art and Zhang Hongxing, Senior Curator of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Also indispensable to my xiii

15 progress: Wang Guangyao and Geng Baochang of the Palace Museum in Beijing; Chen Ruiling of Tsinghua University School of Art and Design; Qin Dashu, Quan Kuishan, and Freda Murck of Beijing University; Shan Guolin of the Shanghai Museum; Lu Lingfeng of the University of Science and Technology of China; Rob Mintz and Bill Johnston at the Walters Museum in Baltimore; and Chen Yuqian of the Jingdezhen Ceramics Institute. Especially crucial to my learning, even today, has been my language teacher, Chou Changjen of the International Chinese Language Program in Taipei. A project about an object of such global scope necessitated funding from many different institutions and sources. I would like to thank the UCSD Department of History, the Needham Research Institute with funds provided by the Andrew Mellon Foundation, and the Blakemore-Freeman Fellowship. Writing, travel, and purchases of expensive digital images were also supported by the UCSD Chinese history program and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation. I am amazed that I have such loving friends and family and I hope that I can be the same for them. I will start by buying them Precious pots and pans from Jingdezhen. Christopher Lee, professor at University of British Columbia, has read chapters at last minute requests. Jeremy and Aileen Kua provided housing during exigent times. Jeannette Ibarra deserves special mention for making San Diego a home during the times that I am here. My parents and my brother provided the most support of all and to them this dissertation is dedicated. xiv

16 VITA 2000 Bachelor of Arts, Yale University 2004 Master of Arts, University of California, San Diego 2008 Doctor of Philosophy, University of California, San Diego FIELDS OF STUDY Modern Chinese History Modern East Asian Art History Professors Kuiyi Shen and Norman Bryson Studies in Pre-modern Japanese History Professors Takashi Fujitani and Stefan Tanaka Studies in Pre-modern Chinese History Professors Suzanne Cahill, Marta Hanson, and Weijing Lu Studies in European Intellectual History Professor David Luft xv

17 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION China s china: Jingdezhen Porcelain and the Production of Art in the Nineteenth Century by Ellen Huang Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, San Diego, 2008 Professor Joseph W. Esherick, Co-Chair Professor Paul G. Pickowicz, Co-Chair My dissertation examines the interaction between global political-economic transformations and changing concepts of Chinese art in the nineteenth century. Its focus is on the porcelain from the renowned “porcelain city,” Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province of southeast China. Jingdezhen has been the center of world porcelain production since the thirteenth century. Although Jingdezhen s porcelain industries experienced tremendous changes and upheaval during the nineteenth century including expanding overseas trade, decimation by the Taiping rebels in 1853, reinstatement of imperial patronage by the Qing Court during the Tongzhi Restoration scholars of science, art, and Jingdezhen history alike rarely investigate this period. Contrary to scholarly consensus, the xvi

18 nineteenth century witnessed a surge in the production of texts and visual images detailing the aesthetics, technology, and manufacturing of Jingdezhen porcelain. This study focuses on the systemic production of knowledge about a material object – Jingdezhen chinaware – by tracing the global trajectories of key documents and visual images on porcelain that circulated within and across boundaries of such places as China, France, and Japan. I will highlight the circulation of such texts and visual images at crucial historical junctures of the nineteenth century, concentrating on periods of industrialization, inter-state conflict, and changing trade patterns. Thus this project will attempt to articulate the global and political processes that negotiate and re-position an object s materiality specifically the materiality of Jingdezhen porcelain in relation to its visual and textual aspects. By historicizing the discourse and practices of a specific object of trade and art, especially one that was and remains closely associated with a particular place and culture, I examine how concepts of self and other find material embodiment through representative objects of culture and exchange. xvii

19 Introduction Some 300 miles southwest of metropolitan Shanghai lies Jingdezhen (Map 1). Surrounded by rocky granite, mountainous terrain and the two river valleys of Xinjiang and Raohe, the city is located in the minerally rich alluvial plains of Jiangxi province. Historically, Jingdezhen was considered to be part of the heart of the agriculturally productive region the lower Yangtze River valley. Jingdezhen lies on the Cheng River, just east of Poyang Lake, linking the city to Jiujiang. During the Qing dynasty ( ), Jiujiang was a busy Yangtze River customs station (Map 2). After the defeat of the Qing by British troops in 1861, it became a treaty port. Although it was one of the most important economic market towns of the region, Jingdezhen was never the seat of local government during the imperial period. The county (xian) magistrate sat at Fuliang, a walled town just north of Jingdezhen that was also located on the banks of the Cheng River, while the higher level of officials, the prefectural (fu) officials, were based at Raozhou at the point where the Cheng rushes into Poyang Lake (Map 3). 1 Since the eleventh century, the city of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province has been the world s largest and primary producer of porcelain. Its inland location shielded the city and environs from major battles, overland adversaries, and attackers from the eastern coast. At the same time, its proximity to major water transport and communication channels integrated the city to larger trading and economic networks. For 800 years, the hundreds of kilns at Jingdezhen have produced porcelains for domestic use as well as for export use all 1

20 2 around the world. Since the Yuan dynasty, the kilns were for the most part run by government officials who oversaw hundreds of craftsmen. Artisans and potters specialized in throwing, mold production, underglaze design painting, overglaze enamelling and calligraphy. These craftsmen were also helped by less skilled workers who prepared the clay and transported the finished pots to the Cheng River for shipping. By the early eighteenth century, porcelain produced in Jingdezhen had already attained such worldwide prestige that it comprised an important part of China s growing export economy. Between 1719 and 1833, foreign ships trading at Canton (Guangzhou), which was directly connected to Jiujiang via the Gan River and the Qing dynasty s primary trading port and only legally endorsed entrepot after a Qing court imperial decree in 1759, increased thirteen-fold over a period of approximately a hundred years. 2 The remains of a sunken Dutch East India Company cargo ship en route from Canton to Batavia (present-day Jakarta) recovered in 1984 contained at least 140,000 pieces of porcelain, the most of any type of good on board. 3 Jingdezhen exported several million pieces to European markets annually, a trade advantage that compelled the domestic transit taxes at the port of Jiujiang to be the highest in the empire, benefiting the dynasty and the Jiangxi Yangtze region in general. 4 Porcelain, along with tea and silk, played a role in shaping a global trade system in which the net trade balance favored China. 5 Beside economic aspects, Jingdezhen porcelain also carried cultural weight. In light of the myriad pieces of porcelain in maritime Southeast Asia, Europe, and coastal East Africa that feature combinations of patterns and ornamental designs of multiple geographic origins, historian Robert Finlay has identified porcelain as a primary force in the creation of a global culture in the early modern era. 6 Indeed, Chinese porcelain had become such a desired material that it was an object of fixation for princes,

21 3 kings, and chemists in places as varied as Saxony (in modern-day eastern Germany), Istanbul and Paris. 7 Jingdezhen did not only export porcelain wares. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, several fervent attempts to uncover the secrets of porcelain s composition and production had already occurred. This lead to the development of a verifiable economy of knowledge about Jingdezhen porcelain in the eighteenth century which expanded through the nineteenth. 8 Circulation of this knowledge was also global in scope. Ideas about porcelain traveled in the forms of textual documents and visual illustrations. An important episode of information exchange that highlights this obsession with unlocking the secrets of porcelain was the publication of two letters dated 1712 and Written by Pere Francois Xavier d Entrecolles, a French Jesuit missionary who lived variously in Beijing and in Jiangxi province between 1698 and 1741, the letters were based on his eyewitness observations of porcelain production techniques, culled from his many excursions to Jingdezhen. A famous early description of the unceasing and industrial kiln production activity ongoing at Jingdezhen came from d Entrecolles letters: tens of thousands of pestles shake the ground with their noise. The heavens are alight with the glare from the fires so that one cannot sleep at night. 9 The result of his spying was the first major Western-language description of porcelain manufacture to reach Europe, the publication and widespread dissemination of which further fanned the craze for knowledge about porcelain production. After he sent his letters as reports to his diocese in Europe, the letters reached readers and art lovers almost immediately. His observations of the production process at Jingdezhen were published in both English and French-language books in 1717, 1735, and In the nineteenth

22 4 century, these volumes continued to receive much attention in the growing scientific, industrial and artistic quest for knowledge about Jingdezhen porcelain. 10 For example, the British school administrator, historian of science, and amateur potter Simeon Shaw mentioned Father d Entrecolle s trip and findings in his influential chemical analysis of porcelain in Shaw established nineteenth century pottery institutes in England and was active in promoting the craft of porcelain. He also wrote a history of the famous Staffordshire pottery factories founded by Josiah Wedgewood in the second half of the eighteenth century in industrializing Manchester. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, Stephen Bushell included a reprint of d Entrecolles reports as an appendix to his 1890s translation of a late eighteenth century Chinese language monograph on porcelain. 11 People living in Europe were not the only ones interested in porcelain production. Nor were missionaries from France the only writers who produced knowledge about porcelain manufacture. Indeed, while Pere d Entrecolles did not cite references in his letters, he supplemented his first-hand observations with information gleaned from Chinese-language sources and images, including a Yuan dynasty literati account of porcelain that was recorded in several Qing dynasty versions of Fuliang county gazetteers. 12 In fact, as this dissertation will show, Qing emperors were also eager to learn about the making of products integral to the territory they controlled, including porcelain, rice, and silk. 13 Moreover, imperial curiosity actually materialized in visual and textual form, contributing to, and in some cases encouraging, the networks of exchange in porcelain knowledge.

23 5 My dissertation examines the circulation of knowledge about porcelain in order to explore how china (porcelain) became a quintessential symbolic marker of the nation of China during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a time period when this network of knowledge exchange flourished. By the end of the nineteenth century, texts and images about porcelain from Jingdezhen had surged in numbers, circulating in and beyond Qing territorial boundaries. In order to advance my research, I trace the history of three major texts and one set of album paintings that have become the very basis on which collectors and specialists have come to understand Jingdezhen china. Knowledge about porcelain, the context in which it was produced, and the nature of that knowledge are the primary foci of my inquiry. The first chapter focuses on the first international exhibitions of Chinese art, in three different cities between 1935 and The impetus for the massive exhibition came from a group of writers, collectors, and Chinese art scholars based in London. The usual scholarly focus has generally zeroed in on the London showing of the objects, the majority of which were Jingdezhen porcelain objects. The London International Exhibition of Chinese Art, held from November 28, 1935 to March 7, 1936, was the first exhibition of Chinese art to showcase a large quantity of artifacts from the newly established Palace Museum in a venue outside of China. Initiated by English collectors, the event was co-sponsored by the Chinese government, then led by the Nationalist Party. There was also a preexhibition in Shanghai and a post-exhibition in Nanjing, where the objects sent by various Chinese institutions were shown to the public at home. The importance of these three separate showings of Chinese art to the development of knowledge about porcelain cannot be overemphasized. Together they provided the context in which Guo Baochang,

24 6 one of the most important specialists on porcelain in the late Qing dynasty and first half the twentieth century, worked. Through the forum of the exhibitions, Guo s essay, Brief Description of Porcelain (Ciqi gaishuo), was translated, printed in exhibition catalogues, sent to English collectors and educators, and used by twentieth century specialists in art history to write about Chinese ceramics. There was also the practical fact that Guo was responsible for the selection of porcelain objects sent from Beijing to be displayed in the various exhibition venues. While the discursive framework surrounding the discussions and representations of porcelain was certainly nation-centered, the event s publicity generated an unprecedented opportunity for the influence of Guo Baochang, whose views and intentions combined imperial, national, and personal objectives to put forth a narrative of porcelain history centered on falangcai enameled porcelain and the brilliant imperial porcelain commissioners (dutaoguan). Clearly, we know that the story ends with porcelain emerging as a national icon, but it begins with a book published in the early nineteenth century. The second chapter of the dissertation moves backward in time to the beginning of our story in order to consider the first specialized book on Jingdezhen ceramics, the Jingdezhen Tao lu. Writing of the book began in the 1790s but its first publication occurred in The final form consisted of an important first chapter (juan) that included the woodblock printed images portraying porcelain production, which also made the Jingdezhen Tao lu the first illustrated manual on Jingdezhen porcelain. The book s nineteenth century circulation history demonstrates that the history of its reception and of porcelain s canonization is unique. The book was translated at the height of the western industrial intrusion into Qing territory. Both instances of its translation occurred in the middle of

25 7 modern war and foreign attempts to gain power through territorial, scientific, and economic advantages in terms of production, trade, and goods: the Opium War of the 1850s, and the Sino-Japanese war of Yet, as the book s publication history shows, the subject matter of a book varies according to the different objectives of the key people and institutions involved. The original authors were themselves writing and illustrating for their own purposes; the 1815 author, Zheng Tingui, reconfigured the text and added images because he was responding to earlier texts and ideas about porcelain that originated in the inner court of the Qing central government. Thus, Jingdezhen Tao lu s history shows that porcelain was a site of negotiation and intellectual contestation, that a book is not a one-dimensional channel of truth, and that the resultant images of Jingdezhen sprung from the interaction between court initiatives and local activity. The third chapter continues along this theme of court and local interactions, but presents an extended discussion on the role of visual images in the understanding of porcelain. More importantly, it is an exploration of the nature of knowledge, representation, and understanding itself. The chapter analyzes the different types of visual representations of porcelain and demonstrates the advent of porcelain production images constructed as sequentially viewed painting sets made for the emperor. By the 1730s there may have been as many as three separate imperial court albums depicting the steps of porcelain manufacture in the form of ordered painting albums for the Qing court. It was, however, a crucial Qianlong edict that instigated their textual annotation by Tang Ying, a project completed in 1743 that directly influenced the writing of Jingdezhen Tao lu and later translations and pictures of imperial kilns. These porcelain manufacturing albums not only exemplified the Qianlong emperor s keen interest in the detail and

26 8 technique of production, they also showed how porcelain was an object portrayed as the sum of its parts. In this sense, Qianlong s visual representations of porcelain were a part of a larger mission to transmit an emperor-centric omniscience and ubiquity, also a phenomenon exemplified by court art collecting and vigorous cataloguing efforts. Similar aesthetic modes, reflected in export paintings and imperial albums, traveled the global stage at roughly the same time but for very different purposes. This chapter presents an outline of this simultaneous global visual culture of porcelain. The last chapter brings us to the end of the nineteenth century with an analysis of the views of a late-qing collector and official, Chen Liu. His text on porcelain, Tao Ya, was both an aesthetic and social commentary. Over two-hundred pages long and written in literary Chinese, Tao Ya was most influential for later studies focusing on the history of porcelain in the Qing era, especially the reigns of the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors. Without any systematic organization, the author s thoughts on porcelain glazes, their appearance, the nature of porcelain bodies, foreign tastes, international expositions, and instructions about identifying fakes form a hodgepodge of notes and come together to form his tome on ceramics. The chapter sifts through his morass of opinions and observations in order to shed light on his social commentary, which reveals an internationally informed porcelain appreciator. His views revealed an epistemological framework embedded in modern notions of time and focused on the present and future possibilities of his society and porcelain. While his subject matter made him look like an antiquarian, Chen was not a man who wanted to remain in the past. I show how the actual conditions in which he lived enabled him to view and judge porcelain, including the forced opening of imperial palace collections. Ultimately, the

27 9 chapter demonstrates how ideas about porcelain were historically grounded in momentous events of the late Qing global setting, how Chen erased entire genres of porcelain history, and how foreigners came to overlook Chinese voices that were speaking at exactly the same time the global canon was being constructed. The chapters that follow examine a series of texts and visual images as case studies. They were disparate in their moments of production, related in their later applications and appropriations, and in hindsight, linked to a much broader historical process. They are important signposts of the nineteenth century journey that ended with the canonization of porcelain. They reveal an object that seemed to be everywhere and everything to many people. 1 Fuliang county has changed its name many times. In the Han dynasty it had no separate existence but was part of the larger county of Poyang. It became a county in its own right in the Tang dynasty, as Xinping, but was later called Xinchang and eventually Fuliang. It probably refers to a bridge which crossed the Cheng river at some point in time. It retained its links with Raozhou (formerly Poyang) as a part of the Raozhou prefecture in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Zhongguo gujin diming da cidian [Dictionary of Chinese Place Names Old and New] (Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1933), Susan Naquin and Evelyn Rawski, Chinese Society in the Eighteenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 103, Table 2. 3 C.J.A. Jorg, Porcelain and the Dutch China Trade (Martinus Nijhoff: The Hague, 1982). Colin Sheaf and Richard Kilburn, The Hatcher Porcelain Cargoes: The Complete Record (London: Phaidon, Christies 1988), Naquin and Rawski, Chinese Society in the Eighteenth Century (1987), 162. The woodblock illustration is wrongly attributed to an 1815 edition of the main text or book under discussion in this paper. 5 Naquin and Rawski, 104. Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000),

28 10 6 See Andre Gunder Frank, ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998); Robert Finlay, The Pilgrim Art: The Culture of Porcelain in World History, Journal of World History 9.2 (1998): Janet Gleeson, The Arcanum (New York: Warner Books, 2000). 8 In Joseph Needham and Rose Kerr, eds., Ceramic Technology, Science and Civilisation in China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), See the references to Gaspar da Cruz s short notes on porcelain and their place of origin, remarks by Juan Gonzalez de Mendoza, and short passages written by the German Jesuit, De Mandelslo in Quoted in Mark Elvin, Pattern of the Chinese Past (London: Methuen, 1973), Pere D Entrecolles excerpts were published in J.B. du Halde s Description Geographique de l empire de la chine (1735) in Chapter 2, and R. Brookes, The General History of China (1736) Chapter 2, The letters were published along with other letter reports written by Jesuits in the mission fields under the name Lettres edifiantes et curieuses (Paris, 1717) in volume 7, 253; a second edition appeared in A copy of Lettres are in the British Museum. For the precise reference, see N. J. G. Pounds, The Discovery of China Clay, The Economic History Review 1:1 (1948), Simeon Shaw, Chemistry of Porcelain, Glass, and Pottery (London: Vos Nostrand, 1900[1837]), 399. Stephen Bushell, Chinese Pottery and Porcelain (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910), See for example, the Ceramic Memoirs (Tao ji) as noted in the 1682 and 1742 editions of the Fuliang county gazetteer in Needham and Kerr, Ceramic Technology (2004), 24, fn.112 and Huang Zhimo 黄, Xunmin tang congshu 6 vols. (n.p.: Huang, ). 13 Imperially Commissioned Pictures of Tilling and Weaving, in Chinese Rare Books in American Collections ed., Soren Edgren (New York: China Institute, 1984),

29 11 Map 1. Jingdezhen kilns location Adapted from: Julie Emerson, et al., Porcelain Stories: From China To Europe (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 2000), 46.

30 Map 2. Jiangxi Province Jingdezhen, Lake Poyang, Cheng River, Jiujiang, and Nanchang indicated. 12

31 13 Map 3. Qing period (1820), northern Jiangxi: Jingdezhen, Fuliang, Raozhou prefect Adapted from: Zhongguo lishi ditu ji, Qing shidai, eds., Zhongguo shehui kexue yuan (Beijing: Zhongguo ditu chubanshe, 1987).

32 1. Guo Baochang, Porcelain Objects, and the First International Exhibitions of Chinese Art, The London International Exhibition of Chinese Art, held from November 28, 1935 to March 7, 1936, at London s Burlington House of the Royal Academy of Art, was a landmark event in the exhibition history of Chinese art. 1 As the largest exhibition of Chinese art ever to be organized – the total number of exhibited objects amounted to 3,080 objects – its worldwide significance lies in the fact that it was the first exhibition to showcase objects outside China from collections of the former imperial palaces, then already reconfigured as the Palace Museum (Gugong ) in Beijing. Of the three thousand objects lent to the exhibition, approximately a third of the artwork came from China s various art institutions. Of the 984 objects on loan from China, 735 objects originated from the Palace Museum s imperial collection. The majority of the artwork came from three sources: the Chinese government, the British Museum s Eumorfopoulos Collection, and Percival David s collection of Chinese art. It was also the first exhibition of Chinese art to have garnered international cooperation – the galleries included items from public institutions and private collections in the United States, Germany, India, Russia, France, Holland, Belgium, and, after some prodding and convincing, Japan. 2 During its three-month duration, the exhibition attracted a viewership of 420,048 people and earned over 47,000 English pounds. 3 Major print media publications in the English and Chinese languages, such as London s The Times and Tianjin s Da Gongbao (L Impartial), covered the event, even publishing special issues devoted to the exhibition. 4 Observers declared it a success for opening the 14

33 15 world s eyes to Chinese art. Madame Guo, wife of Guo Taiqi, Chinese foreign minister to England during the 1930s, declared: The International Exhibition of Chinese Art, which opened in London on November 27, 1935, formed one of the most remarkable collections of art treasures ever seen. It illustrated the culture of my country over a period of nearly 4,000 years. 5 John C. Ferguson, an American living in Beijing who was also at the time an advisor to the Chinese organizing committee of the exhibition, described the exhibition s success in terms of its ability to attract large crowds which filled the halls to overflowing. 6 Clearly, scholars, experts, and government officials active in the 1930s recognized immediately the importance of the London Exhibition. Recent scholarship has echoed those reviews by remarking upon the exhibition s significance in stimulating public and academic interest in Chinese art history. 7 Yet, despite this event s prominence in the scholarly literature, few scholars have studied the exhibition s discursive output. As such, few if any recent scholarly articles mention the varying perspectives on art and the exhibition from China-based commentators responding to the event. Instead, the current scholarship relies upon London-based, English-language primary sources alone to reconstruct the historical event. In doing so, these approaches obfuscate the exhibition s factual history and overlook the exhibition s first and final instances of public display – the Chinese government s selection of objects was shown first in Shanghai in a preexhibition between April 8, 1935 and May 5, 1935 and then, upon the objects safe return to China, exhibited again in a post-exhibition at the Nanjing Mingzhilou Exhibition Hall (Nanjing Mingzhilou kaoshi yuan ) for three weeks between June 1 and June 22, Given the sheer number of art objects on display on loan from

34 16 institutions from China, including the Palace Museum, Henan Museum, and Academia Sinica, the elision of Chinese perspectives and sources is even more unjustified (Figure 1). 8 Along with the London display, the preliminary exhibition (yu zhan), while unmentioned in most English-language accounts of the international exhibition, generated much attention in the Chinese press and had a daily attendance of nearly 3,000 people. 9 Both of the largest circulating newspapers in Shanghai, Xinwen bao and Shenbao, reported each day on the pre-exhibition, noting attendance numbers, visits by famous people, and viewers opinions. 10 The Shanghai pre-exhibition attracted visitors from such art societies as the Bai E Painting Society, Wan Mi Shan Fang Painting Society, Xinhua Professional Art Academy, and Hangzhou National Academy of Art. 11 Shenbao, a newspaper from Shanghai boasting some of the largest circulation numbers, reported that a number of famous painters, and archaeologists came from places outside of Shanghai to view the exhibit. 12 In all, attendance for the preliminary showing in Shanghai reached 40, The Ministry of Education and the Chinese Organizing Committee issued catalogues in both English and Chinese as viewers guides: the Chinese-language catalogue cost half a dollar and the English version sold for one dollar. The Ministry of Education, on the day of the opening ceremonies for the Shanghai pre-exhibit, even presented the two versions as gifts to the special guests in attendance. 14 These guests included officials and luminaries in government and cultural circles from in and outside China, including Cai Yuanpei, Dai Jitao, Wang Jingwei, Yu Youren, and the ambassadors from foreign countries stationed in China. The catalogues included photos of each artwork and a caption that identified its date of creation, informing viewers how to view, see, and understand the art objects

35 17 before them. One could even order the catalogue by mail. 15 For the Nanjing postexhibition showing, the Ministry of Education reprinted the four-volume catalogue through the Commercial Press. The sale price was set at five dollars. As a newspaper announcing the catalogues publication reported, Since not everyone could view the exhibit in Shanghai and London, and furthermore the Nanjing exhibit could only reach a certain number of eyes, this catalogue is now reissued and can reach a wider viewership. 16 Thus, in light of the large numbers of actual viewers and the broad dissemination of multiple editions of the exhibition catalogue, the scope of the exhibition could be said to encompass major urban centers both inside and outside of China. A copy of the four-volume catalogue sponsored by China s Ministry of Education, containing all the government objects sent to England, was presented as a gift to one of the English committee organizers, Oscar Raphael, by the Minister of Education, Wang Shijie, in 1936 (Figure 2). In light of the publicity and publications it generated, and as the first and largest of its kind, the exhibition played a vanguard role in shaping and defining China and art. In view of such an outpouring of printed sources, this chapter examines the discussion about the exhibition and concepts of Chinese art as generated by the exhibition. It highlights the groundswell of ideas about Chinese art by including views and sources written by non-western viewers and organizers in order to give a more balanced historical account of the exhibition. For the purposes of this dissertation, it establishes the context of divergent discussions during the 1930s on porcelain and art in China among Western collectors, Chinese researchers, and Nationalist Party officials through a focal

36 18 event in Shanghai and Nanjing. It was a venue in which porcelain was the most numerous and perhaps prominent of all object types displayed. A central figure in this story will be Guo Baochang. It includes an account of his artistic productions, cross-cultural relationships and his writings authored as the last Jingdezhen porcelain commissioner, or what Chinese language scholarship often refers to as dutaoguan. 17 Guo produced over 40,000 porcelain objects for use in Yuan Shikai s imperial palaces. 18 He was the person in charge of selecting the porcelain objects for the 1935 exhibition in London. I will analyze his account of porcelain history in an essay published widely through periodicals as well as through personal gifts to art collectors in the United States and England. He was on friendly terms with exhibition organizers and advisors from Great Britain and the United States, including the famous porcelain collector and exhibition chair, Sir Percival David, and longtime Beijing resident, researcher of Chinese art history, and Guomindang advisor, John Calvin Ferguson (Figure 3). 19 This section begins by tracing the process of organizing and exhibiting Chinese art, including the stated goals and organizing principles that set the institutional framework through which porcelain objects from the Palace Museum collection in Beijing could play an important role in configuring national art during the early twentieth century. Starting with the planning of the exhibition and tracking the objects movement from Shanghai to London, I analyze this event as an important instance of 1930s Republican-era efforts to build, through visual displays, a public awareness of national art history through the maneuvering of material objects. By tracing how the exhibit s objects were presented, represented, and understood in various public spaces, including print

37 19 media, museum catalogues, exhibition reports, and academic discussions on Chinese art, I hope to illuminate the social and political forces at play in the acts of displaying, viewing, and enjoying aesthetic objects. Ultimately, exhibiting China was not without contestation, demonstrating the instability of the concept Chinese art. The second half then considers the central role of Guo Baochang, the technical committee member and porcelain expert chosen by the exhibition s organizers from China. Guo was responsible for the porcelain objects sent to London, and in the final section of this chapter, I will examine the themes he laid out in his selection of porcelain and porcelain essay, Ciqi gaishuo (Brief Description of Porcelain). I. The International Exhibition: Planning from Beijing to Shanghai to London The idea for a comprehensive display of Chinese art originated in October 1932, with the efforts of five renowned English connoisseurs of Chinese art artifacts. 20 The fathers of the endeavor included R. L. Hobson, a noted researcher of ceramics; University of London Professor Walter Perceval Yetts, whose specialty was Chinese bronzes; Sir Percival David, a wealthy collector of porcelain; ceramics collector George Eumorfopoulos; and Oscar Raphael, a well-known jade collector. In the same vein as prior international exhibitions specializing in a particular nation s art, this exhibition aimed to mark an important stage in European understanding of Oriental, and especially Chinese, art. 21 The English organizers planned to first seek the Chinese government s cooperation in implementing the exhibit, particularly in the selection of art objects from collections in China, and then to entreat the cooperation and participation of various collectors and museums across the world. 22 In the words of Sir Percival David, who later

38 20 became director of the entire exhibition, the art exhibition would bring together the finest and most representative arts and crafts of China from the dawn of its history to the year No explanation for the choice of this particular time span was given. However, this specific temporal framing of Chinese art history does have the effect of erasing the era of violent plundering of art objects and neglecting the rather material issue of how the objects were obtained by Britain s collectors in the first place. 24 This temporal truncation also reinforced the notion that Chinese culture and art after 1800 fell in decline and did not merit attention, a misconception about nineteenth century Chinese art and society that has persisted to this day. 25 Meanwhile, the Chinese Nationalist Government did not find itself in an ideal governing situation in the 1930s. 26 Although it was the heyday of its rule, the central government faced severe challenges, such as factional politics, urban unemployment, revenue collection obstacles, and unrelenting territorial and economic pressure from the Japanese, as witnessed by worker strikes, riots, and the Manchurian Incident of 1931, to name only one incident among many. Economically, the currency, agriculture, and various industries suffered from the effects of worldwide depression underway in this decade. The Guomindang regime was a young national government, coming to power and exacting a purge of some of its political enemies as recently as In short, the challenges of building a nation with all its attendant concerns over public legitimacy remained a priority for the incipient national government during the first half of the 1930s. 27 Thus, when the opportunity to participate in an international exhibition of Chinese art presented itself to the government in October 1934, the Guomindang foreign minister based in London, Guo Taiqi, enthusiastically recommended that the

39 21 Chinese government take part. The Executive Branch of the Nationalist Government, in consultation with Palace Museum director Ma Heng, soon agreed to the proposition. Following the initial acceptance, the Executive Yuan assigned the task to the staff of two government units: the Ministry of Education and the Palace Museum. Eventually, a makeshift Chinese Organizing Committee (choubei weiyuanhui) assumed the overall administration of China s role in the exhibition. 28 Responsibility for the initial selection of objects from China s museum institutions fell upon the Technical Committee (zhuanmen weiyuanhui), a special group appointed by the Organizing Committee. Members of the Technical Committee included staff experts on artifacts and art at the Palace Museum. These noted scholars included researchers in such fields as porcelain and painting, including archaeologist Tang Lan, etymologist and bronze cataloguer Rong Geng, former Jingdezhen porcelain kiln supervisor under Yuan Shikai, Guo Baochang, and art historian and painting critic, Deng Yizhe. 29 Foreign minister Guo Taiqi also specifically initiated the idea of a preliminary exhibition in Shanghai. According to Wu Hufan 吴, a guohua painter based in Shanghai, Guo beseeched the Ministry of Education to organize a preliminary exhibit for the express purposes of publicizing the event and demonstrating to the public such great work (da gong), thus accomplishing two things in a single stroke (yi ju liangde). 30 Guo s comments indicate the exhibition s two-fold purpose. First, the exhibition would educate the public domestically and internationally – in both China and England – about the wonders of Chinese art. Secondly, the safe handling of artworks would increase public trust in the central government s stewardship over national treasures.

40 22 However, some dissenting opinions soon emerged in Beijing and Shanghai regarding the Chinese government s decision to send national treasures (guobao) from the Palace Museum to London for display. 31 Articles in Shanghai-based newspapers reveal anxiety on the part of the reading public over the government s attitude towards cultural property. Some opposed the entire exhibition on grounds that the government was using the event as a pretense to sell off treasures to foreign governments. In order to quell these fears, Minister of Education Wang Shijie (also known as Wang Xueting ), as acting chairman of the Chinese Organizing Committee, stipulated six principles by which the exhibition planning would proceed. First, the British government would provide all costs and funding for a British naval ship to transport the art objects from China. The exhibition items would go directly from China to England without any intermediary stops. Second, the exhibition would be publicized as jointly sponsored by both the Chinese and British governments so as to bring more honor to the event and by extension, the governments. Supervision over the shipping, packaging, and handling of the art objects en route to, from, and in London had to be officiated over by expert staff from China appointed by the organizing committee. Photographs of the illustrated catalogue as well as pre- and post-exhibitions in Shanghai and Nanjing respectively would help assure the Chinese public of the safe arrival and return of the actual objects. The final organizing principle stipulated that the centerpieces of the exhibition would consist of artifacts housed in the Palace Museum. 32 Evidently, for government officials like Wang Shijie, an important objective in participating in this exhibit was not simply to cause Westerners to appreciate the magnificent beauty of Chinese art (shi xifang ren renshi Zhongguo yishu zhi weimei). 33

41 23 The stipulations for the specific use of Chinese experts, photographs, and additional exhibition viewings adhere to Wang s purpose to bolster political legitimacy by increasing the Chinese public s trust in its national government. Zhuang Shangyan (also Zhuang Yan ), one of the two secretaries of the Special Chinese Commission who traveled with the art objects to London, described the purpose of the Nanjing showing as allowing the citizens to confirm the return of the real (shi ) objects. In this regard, the government would be able to demonstrate its trustworthiness (yi zhao xinshi ). 34 The Chinese Organizing Committee also had two main selection principles: only the best things (jingpin ) would be chosen for the exhibit, and any one of a kind (fan zhi you yijian zhi juepin ) would not be included in the selection. 35 A draft list of the artifacts would first be drawn up by the Palace Museum and then examined by a subcommittee of the main Chinese organizing committee. The final selection of items sent from China would be the result of consultations between this subcommittee and a special London committee sent to Shanghai in April By April 19, 1935, the list of selections had been finalized. On June 7, 1935, after the objects had been carefully packaged, they were loaded onto the English naval ship H.M.S. Suffolk. Zhuang Shangyan, the Palace Museum staff leader, and Tang Xifen, an official in the Ministry of Education, accompanied the art works on the ship headed to England s Portsmouth Dockyard (Figure 4). 37 The one thousand or so items were packed carefully into 93 cases. 38 In London they were joined in September by four Palace Museum staff researchers who were specifically assigned to oversee the unpacking and

42 24 correct handling of the objects for the duration of the exhibit: Na Zhiliang, whose expertise concerned jade; Fu Zhenlun, a Palace Museum archaeologist; Song Jilong, and Niu Deming. 39 In London, the exhibition displayed over 3,000 objects, with about a third of the artifacts contributed by the Chinese government. Of the nearly one thousand artifacts shipped to London from China, over 700 came from the Palace Museum, 100 from Rehe Palace (Chengde or Jehol), 100 from Academia Sinica, 14 from the Henan Museum, 50 from the Beijing National Library, and 4 from Anhui Library. Among these national treasures, there were 60 bronzes, 362 ceramic objects, 170 works of painting and calligraphy, 16 fans, 20 furniture pieces, and approximately 10 scholars implements. The Chinese government and Royal Arts Academy of London each received half of the proceeds earned from ticket sales and other revenues – about 9,000 British pounds each. 40 As mentioned, after the objects on loan from the Chinese government returned safely to Shanghai in 1936, they were shown again in the former Examination Hall in Nanjing, then capital of the fledgling republic. Proceeds from the London exhibit went to organizing China s second national art exhibition and constructing a national concert hall and exhibition center, both of which opened in Nanjing in The fact that there was a post-exhibition showing in Nanjing again decenters London as the locus of the event s significance. II. Two Views of Material Artifacts Objects of History: Representing the Nation

43 25 As described in an introductory article written by exhibition director Sir Percival David, Chinese art was guided by an internal attribute of the Chinese and by an inner consciousness of powers and presences mightier than ourselves. 42 In his article, David commented on various pieces of art such as a Shang-Yin bronze, a few scrolls of painting and calligraphy, and clay vessels from Gansu Province. Relying on ideas about a timeless cultural spirit, the article reinforced the role of the art objects as representations of the genius of China. Often this genius or spirit was referred to as spiritual significance, an invention, ideals of its age, or some technique, such as paper making. These artistic attributes were all understood as embodying some underlying Chinese spirit. R. L. Hobson, a well-published researcher of porcelain, demonstrated a similar understanding of art and aesthetics. For him, the artwork on display expresses or gives insight into the mind and character of one of the great races of the world. Hobson drew attention to the meaning behind these artworks as the import of the Exhibition as a whole. His assessment of the exhibition clearly shows a conceptual contrast undergirding his explication of the exhibition and displays of art objects. For him, the art objects were not simply objects of aesthetic pleasure, but the representation of something more meaningful: the genius of the Chinese race. 43 Such ideas about the nature of art objects, and the deeper meaning embedded within them regarding China, reflected Orientalist frameworks of knowledge that included the erasure of history, reliance on essentialist notions of culture, and a modern epistemological bifurcation between object and meanings represented therein. 44 While London gallery placements reflected a

44 26 chronological display, the historical development portrayed neglected the non-national aspects of that history. Objects of the Present: Objects as an Exchange of Tributes As journalistic re-feeds of English quotations via translations in the Chinese press indicate, observers in urban China were aware of British admiration for the Chinese and Chinese art. Articles in the Da Gongbao and Shanghai daily newspaper Xinwenbao, as early as December 1935, printed translated quotations from major British newspapers and periodicals. 45 Chinese officials involved in the operations of the exhibition were cognizant of British opinions but had their own views of the nature of art and displays. Their own comments, as communicated in public lectures and commentaries on the art exhibition, revealed alternative views of the exhibition s purpose and art. One example was a public dialogue between Laurence Binyon, a British Museum senior researcher with expertise in poetry and East Asian art, and the Chinese minister to England, Guo Taiqi. At a luncheon in honor of the exhibition on December 2, 1935, Binyon gave a speech that stressed the meaning of Chinese art in what could be described in hindsight as Hegelian aesthetic terms. Like Hobson and David, Binyon conceived of Chinese art as an expression of another philosophy of life, a genius that lacked what European art emphasized, which was self-aggrandizement and assertion of personality. Again, like the other British collectors and specialists on Chinese art, Binyon highlighted the cultural or deeper spiritual meanings as represented through art.

45 27 The terms pictured the entity of China as a unified, homogenous tradition, often with explicit racial overtones. 46 Guo Taiqi, in a toast given in response to Binyon s speech, discussed the meaning of the art exhibition from his point of view. First, he emphasized that the treasures were sent by the Chinese government with all the goodwill of the Chinese nation. Although some might read this as some form of self-promoting propaganda, what I wish to highlight is Guo s stress on goodwill and the government s purposeful actions. Moreover, his understanding of the exhibition s objects was inseparable from their presentist, exigent political significance. In his view, the very action of sending objects was what mattered. While he emphasized that the collection of objects sent over by the government was designed to illustrate China s cultural development for more than 30 centuries, Guo expressed his hope that viewers would see that Chinese artistic traditions were far from static, and that they would come out of the galleries with the understanding that the objects of art, in style, feeling, and sense of form, [were] remarkably modern. Finally, according to Guo, what drove Chinese art had an important, active role in the present social situation, for Chinese art was a mature and vigorous influence of the creative force that is animating China s present national reconstruction amid unprecedented difficulties. Guo made another point, too. In explaining the meaning of the Chinese government s participation in this art exchange, Guo, as well as his wife Madame Guo, spoke and wrote on several occasions that the art displayed in the exhibition should remind viewers that the Chinese were a pacific people. They were people who upheld the ideals of peace and virtue. While these opinions might also seem to be an

46 28 idealization of their own country – as any good modern ambassador would diplomatically assert in public – what is important is the way in which Guo and his wife conceptually connected these hopes for art s ability to convey peace with the social chaos and political upheaval that were then taking place in China. Thus, for the Chinese ambassador, the artworks were not only national symbols and representations of a cultural history. Art objects were not simply remnants of the past but agents in the present. Works of art were an activity and embodied a force, the significance of which lay in both the changing historical context and the political present. Similar remarks about the nature of Chinese art were made at the opening luncheon by Zheng Tianxi (Zheng Futing), the second of two Special Chinese Commissioners for the exhibition. Zheng noted that the objects had come to England with the goodwill of China, and that such art works were not produced with a bayonet, but founded upon peace, virtue, and affection. 47 III. Material Concerns: Beyond Cultural Symbolism Criticisms of London Exhibition Displays Just as the Chinese foreign minister Guo s comments endowed art with a political role in the present, Chinese artists and scholars also had presentist concerns when viewing the exhibition in Shanghai. Like the British organizers, Republican China s writers, exhibition planners, and art appreciators valued the exhibition s value as a didactic display of a national art and culture. After viewing the pre-exhibit held at the Bank of China building in Shanghai, Ye Gongchuo, a calligrapher, painter, railway official, and future creator of the simplified Chinese script for the People s Republic of China, expressed his hope that this exhibit increase our awareness [of our

47 29 art] and that people who come to watch this preliminary exhibition would develop a mass art (dazhong yishu). 48 Guomindang Administrative Councilor (xingzheng yuan) and guohua art critic Teng Gu encouraged Chinese citizens [to] go and take a look in order to advance their knowledge of [Chinese] history and art. 49 In his written report from London in the Dagongbao, Executive Yuan official Zheng Tianxi stated that a chief aim of the Nationalist government was to publicize (xuan yang) Chinese national art and culture. 50 Clearly, the exhibition s epistemological framework reflected what Timothy Mitchell has observed in modern exhibitions in general, whereby objects embody a deeper meaning. In this case, during an era of active state-led nation-building, these objects were symbols of China. Despite the shared nationalist framework that structured the understanding of the exhibition as consisting of national art objects, differences between the British and Chinese conceptions of Chinese art existed. 51 As the Royal Academy s commemorative catalogue demonstrates, English scholars organized the art objects temporally (Figure 5). The galleries of display in London s Burlington House were categorized first and foremost by dynastic order, with a gallery labeled Shang-Yin-Zhou, followed by a gallery called Wei-Tang dynasties, three galleries identified as Song, a room called Song-Yuan dynasty and another gallery with the heading Early Ming dynasty. Positioning the exhibition displays according to a temporal framework lent themselves easily to understanding Chinese culture as progressing along a linear timeline of development, a hallmark of constructed national identities. 52 By contrast, at the Shanghai preliminary showing, as at the Nanjing show, Chinese display strategies organized art works by

48 30 object category – bronzes, painting and calligraphy, ceramics, and miscellanea (qita ), which included tapestry, embroidery, jades, cloisonné, red lacquer, and ancient books. Temporal order was specified within such object-bound categories. By centering the presentation of Chinese national art by form object the exhibitions in Shanghai and Nanjing had a dual conceptual effect. Chinese presentation strategies promoted a timeless universality of cultural treasures and at the same time portrayed Chinese art proceeding along historical development. The British slighting of the material nature of displayed objects as expressed in display layout bothered experts from Beijing. In his article describing his experience as a keeper of objects sent to the exhibition in London, Fu Zhenlun criticized the British for refusing to display objects from newly excavated sites at Anyang, Henan. Fu noticed that the London display wrongly separated objects from the northwest among six different galleries. His critique might have stemmed from the importance he attributed to the physical location and archaeological origins of artifacts, rather than to their temporal dating. Fu also noted that the British did not include textiles, showed insignificant architectural objects of imprecise dating, hung paintings in the wrong manner, and arranged colophons upside down. To Fu, haphazard placement of art objects did not adhere to exhibition principles (zhanlan yuanze). 53 Thus, Fu s critiques of display modes, alongside Zheng and Minister Guo s emphasis on the movement of material objects illuminate a type of object-oriented thinking that surpassed a conception of objects limited to their status as cultural symbols. Instead, Chinese officials and organizers showed a preoccupation with the objects material and physical aspects – as

49 31 works available for touch, display, exchange, archaeologically discovered, or capable of being damaged. The Material Presence of Art History s Objects The exhibition ignited the enthusiasm of intellectual and artistic leaders in China for the development of a more rigorous and systematic discipline of Chinese art history. To them, art historical research was a practice based on the careful research into real objects. Not surprisingly, while intellectuals in China criticized certain British conceptions of art history such as specific dates and authentications, the same viewers and researchers were also envious of the advanced state of British art historical research. After all, Chinese art history, as a formal discipline, was itself a field of study that developed through a network of nineteenth-century translation and exchange. Even the twentieth-century term meishu did not denote fine arts until its introduction into China through the Japanese translation of the French term beaux arts, first used in Japan in the 1870s in conjunction with the Vienna Exhibition of During the nineteenth century, yishu referred more to skills or technique, and appeared mostly in the titles of courses that taught Western drawing to aid the acquisition of such modern scientific skills as geometry, mechanics, geography, and chemistry. 54 By the 1910s and 1920s, however, emphasis shifted from mere technique to the study of art, art history, and technique as expressions of culture. For Chinese art history specifically, the first Western-language monograph on Chinese art was Stephen Bushell s Chinese Art, written in the last decade of the Qing dynasty and published in London in Bushell s Chinese Art was so popular that a second edition was printed in A French translation appeared in Paris that same year. 56 In 1923, Shanghai s Commercial Press

50 32 published the first edition of the Chinese translation of Bushell s foundational book, Zhongguo meishu. 57 The Chinese translation of Chinese Art achieved the endorsement of Cai Yuanpei, whose role in art education reform and social criticism is well known. The book s appearance coincided with the post-may Fourth frenzied advocacy for new nationalist reforms in educational curricula. Dai Yue, a nationalist art historian active at the height of calls for educational reform (by noted educators such as Cai Yuanpei), was the translator. Bushell s book thus created a founding text on Chinese art and provided the basis of Chinese art historical studies in China. Ironically, Bushell s work would not have been possible without access to the material artifacts themselves, which he and other Englishmen obtained from the antique market that grew out of the increasing circulation of looted and sold objects from imperial palaces in and around Beijing at the end of the nineteenth and turn of the twentieth century. 58 Furthermore, Bushell himself based his seminal study of Chinese art on early nineteenth-century books such as Jingdezhen Tao lu, first published in 1815, which discussed ceramic production and was written by two Jingdezhen residents. Despite the Jingdezhen-based nature of Bushell s sources, the modern academic discipline of Chinese art history – a concept based upon the implication that each national culture had its own artistic tradition – came to China through European works. Therefore, it is not surprising that intellectuals in China both admired and criticized English scholarship. Noticing that the British labeled Gallery 1 Shang-Yin-Zhou rather than the usual term Yin-Shang-Zhou, Zhuang Shangyan declared that the British scholarship on Chinese art was superficial and thin. But even though he claimed that the British were quite immature in matters of identification and display, such as hanging paintings too

51 33 high or upside down, and neglecting epigraphic inscriptions on steles, Zhuang also praised their determination to conduct original research. 59 Concluding that such persistence in academic research was respectable, Zhuang suggested that the Chinese reform their attitudes toward studying their own art history and begin limiting the export of Chinese artifacts. If such action were not taken, Zhuang warned ominously, a day would come when Chinese scholars would have to go to foreign countries to study their own artifacts. Writers and artists such as Teng Gu, Ye Gongchuo, and Wu Hufan lauded the effect of museums and exhibitions such as the Shanghai pre-exhibition in furthering art historical scholarship in China. 60 After he viewed the Shanghai exhibition, Teng commented, our government and academic organizations should promote this kind of work more often. 61 Realizing their own country s methods of display lacked a systematic approach further fanned the flames of interest to build the discipline. 62 Wu Hufan urged: This type of activity should be encouraged by the government so that our country s art can bring its honor to the world s arts. 63 According to such artists and scholars, only with proper institutions such as museums and exhibitions devoted to expanding, safekeeping, categorizing, and displaying of material collections could Chinese scholars conduct adequate scientific research in art history. Furthermore, as Wu Hufan and Ye Gongchuo envisioned, art-historical knowledge and the establishment of proper cultural preservation organizations such as museums and exhibitions were integrally intertwined because the spirit of the nation is always connected to its historical cultural artifacts (wenwu ). 64

52 34 Themes of national pride and a desire to preserve and study one s own national tradition in this period are not surprising given the prevalence of nation-centered reform in twentieth-century China. What is significant is how art leaders in China emphasized the importance of the physical materiality of objects to the study of China s art history. A Chinese article introducing a seminal book on Chinese art published by the Burlington Magazine of the Royal Arts Academy in 1935 declared it enlightening for those wanting to understand Chinese art history because Westerners base their academic research on physical contact with the real things (shiwu ). 65 Comments by Palace Museum organizers and the Organizing Committee about the process of lending art works also revealed a similar logic hinged upon the centrality of physical and material aspects of objects. An example of this is evident in the way in which members of the Chinese organizing committee worked meticulously to implement measures that protected the materiality of these objects. For instance, in his report, Zhuang Shangyan went to great lengths to explain the use of multiple layers of velvet bags, cotton cases, wooden crates and finally steel cases to prevent any material damage from occurring during the acts of transporting, packing, displaying, and storing. 66 Even John C. Ferguson, an art collector, dealer, Executive Yuan consultant, and a one-time advisor to the Qing court, observed that Unusual care was taken in their shipment so as to insure their safety. 67 Realizing that the object s correct and proper transport could substantiate the responsibility of the new Republican government over all things related to the nation, Chinese museum scholars and researchers thus attached extreme importance to the objects fragility and substantive condition. In so doing, their concerns illuminated the Chinese organizers preoccupation with the materiality of the sent objects.

53 35 Modern Art History and a Discourse of Material Absences Besides emphasizing the artwork s physical properties, Chinese organizers and viewers were more sensitive to issues of material loss and physical absence that arose from historically specific circumstances. Rather than using aesthetic terms, reporters imbued objects with the value of rarity. Newspaper reports attributed the high attendance to people seeking to see rare collections of treasures (xishi zhencang.). In press articles and viewer s comments, these things were variously referred to as precious objects (zhen pin), or cultural artifacts (wenwu), and national treasures and collections (guobao cang). Xu Beihong, the famous modernist painter and art theorist, defined what he saw at the preliminary exhibit as national treasures because they were all historically rare things (lishi shang xi you zhi wu ). 68 Exalting objects of an art exhibition as rare is not uncommon in the language of marketing. Like the mentality of capital and microeconomics, the urgency of scarcity marks the work of art critics and also drives today s art market. The theme of scarcity did not always mark characterizations of art, as will be shown in the next chapter s analysis of a historical record written about Jingdezhen porcelain just over a hundred years earlier. Still, anxieties about rarity and loss had their origins in historical precedents. One article in the journal Peiping Chronicle in January of 1935 narrates a point of contention between Chinese artists and intellectuals about the loan of objects to Britain. As the report indicates, a group of Chinese cultural figures, including Liang Sicheng, the architectural preservationist, his wife Lin Huiyin, Chen Chung, Dean of Public Affairs of National Tsinghua University, Mr. Hsiung Fu-hsi, a Chinese playwright,